Are Gringos to Blame for Mexico City's Housing Crisis?

Everyone’s talking about digital nomads — but not about what matters.

“Make Mexico spicy again,” read the neon-colored posters plastered along the walls of Roma, Mexico City’s ground zero for the global long-stay tourism wave. In Roma, as well as in the neighboring areas of Condesa and Juárez, it is becoming increasingly common to find restaurants that cater to foreigners, serving non-spicy "Mexican" tacos at prices that are often equivalent to half a day’s minimum wage.

Source: @LQMCC & @isabellamoncayo

The posters are part of a backlash. A campaign against the tidal wave of digital nomads who have settled in the city in larger numbers since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For many Mexicans, foreign arrivals are seen as the main culprits behind soaring housing costs.

But the story isn’t that simple. And blaming the gringos for the housing crisis actually lets the real culprits off the hook.

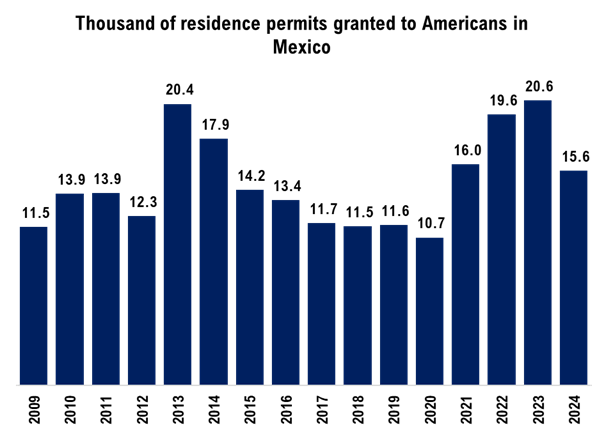

Yes, there are more Americans living in Mexico. In 2024 alone, at least 15,000 U.S. citizens applied for residency, a jump of 34% from pre-pandemic levels. But it’s still fewer than those who came a decade ago.

Source: Mexico’s Migration Policy Unit

It’s also true that housing prices have risen. Over the past two decades, they’ve increased by a staggering 286% across Mexico.

No gringo-made crisis

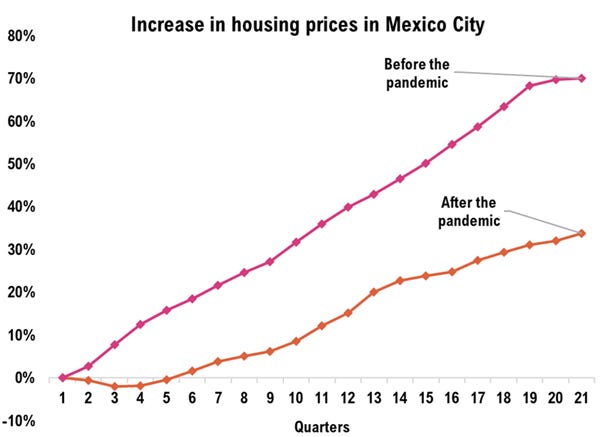

But the data doesn’t support the idea that this is a gringo-made crisis. According to the Federal Mortgage Association, prices in Mexico City have actually grown more slowly since digital nomadism took off. Since 2020, housing costs in the capital have risen just 34%, about half the 70% increase seen in the five years before the pandemic.

Source: Federal Mortgage Association

Housing prices have been increasing everywhere in Mexico, not just in the tourist areas. In the state of Nuevo León, far from any digital nomad hotspot, prices went up 288%. In fact, no Mexican state has seen housing increases under 200% during that period.

The real problem is that Mexico isn’t building homes. Not nearly enough. In the early 2000s, housing construction was restricted to just four of the city’s sixteen boroughs. The prevailing policy was to expel working-class families to far-flung suburbs like Chalco or Tecámac, while the city core was frozen in time. Today, estimates suggest Mexico City needs at least 11,000 new homes each year. Some experts say 50,000. Yet in 2024, only a fraction of that was built. And just 31% of those were considered affordable, priced below $39,000 USD.

The reason only expensive housing is being built is because housing developers can’t make the numbers work any other way. A construction project that takes two years must yield at least a 17% profit to compete with what investors would earn by putting their money in government bonds. The core issue, then, is that it should be possible to build complete homes for under $33,000 USD. Building housing at that cost is extremely difficult in Mexico for reasons that have nothing to do with the gringos.

The real obstacles

The real obstacles are Mexican monopolists, the government’s inability to tax the rich, and the criminal lack of planning by Mexico City’s authorities.

First, many construction inputs are expensive because they’re sold by companies with market power. Take cement, for example. Last year, Mexico’s cement giant CEMEX posted record profits. Its market power is so overwhelming that when it announces a price hike, Mexican builders are forced to cut their public works budgets — they simply have no other supplier. Efforts to import cheaper cement from abroad have been smothered by lawsuits, red tape, and embargoes.

Then there’s the issue of permits. Developers routinely set aside around $59,000 USD per site just to cover licenses and paperwork. These costs are so high because city governments treat permit fees as cash boxes. An easy, discretionary source of revenue that avoids the political risk of taxing the wealthy.

But at the root of it all is a deeper failure: the absence of any coherent vision for a livable, inclusive city. What makes Roma and Condesa so attractive isn’t just their location. It’s their design. Walkable streets, leafy parks, shaded plazas. That way of life is nearly impossible to find in other parts of the city. Mexico City desperately needs to convert empty lots and giant parking spaces into parks, creating shaded pedestrian corridors, reforesting neighborhoods.

The city’s own constitution calls for a land-use plan and a development plan. Neither has been implemented. Without a plan, the city sprawls wherever a developer buys land. Permits are granted by favors. Concrete spreads, green spaces shrink. To fix this, the government must invest in public housing, progressive taxation, and new zoning codes. It must penalize vacant homes and end speculative hoarding. If people don’t live in the houses they own, they should pay taxes for it. Full stop.

For now, gringos will probably remain arriving in Mexico City. You can spot them easily because on days that feel mild, or even a bit cold for the average Mexican, Americans are wearing shorts.

“They get on their bikes in flip-flops, wearing red floral bermudas shorts,” explains Rafael Pérez, a resident of Condesa. “I used to buy tortas de jamón from Don Pepe,” he says, irritated, “but now, local businesses have been replaced by gringos on bikes who are convinced they live in the tropics.”

This piece is an update to “Gringo Go Home,” a text I originally published in El País.

Great piece! Gentrification is a complex and well-studied phenomenon that goes far beyond wealthier foreigners moving into cheaper countries. David Ley’s cultural approach describes it as an organic process seen in cities worldwide, where neighborhood demographics shift in stages: first come artists, drawn by low costs and uniqueness; then middle-class professionals seeking cultural capital; and finally, higher-income professionals, bringing reinvestment. In Mexico, this process in neighborhoods like Roma and Condesa began long before digital nomads arrived. The original gentrifiers were, in fact, Mexican.

Economists like Neil Smith and Tom Slater offer another view, focusing on cycles of urban valuation and devaluation. Investment in a neighborhood is only profitable up to a point. Once returns decline, capital moves elsewhere, allowing the area to devalue until reinvestment becomes attractive again. In Mexico City, central neighborhoods declined in the late 20th century due to rent control, decentralization, and the 1985 earthquake. By 2000, reinvestment began, marking the start of today’s gentrification cycle in the boroughs you mentioned.

As you point out, this reflects a broader crisis in urban planning. The shortage of housing is a key issue, but I believe it’s not just about quantity. It’s about building homes where people can actually live without extreme commutes. Solving this will require a restructuring rooted in what, as you’ve shown, has long been missing: a coherent vision for a livable, inclusive city. This is such an important issue, and more people should be engaging with it in all its complexity. Kudos to you for doing just that.