How Mexicans Get Rich

The Mexican dream exists—but it is narrow, selective, and generally involves only two paths.

In Mexico, most of the rich were born that way. Inheritance, not innovation, remains the dominant route to wealth.

But what about the exceptions? What about those who did not start life in the upper classes and still managed to break into the top 5% of earners?

I analyzed the new social mobility survey of Espinosa Yglesias Centre, a think-tank in Mexico City, to understand the paths followed by the small subset of Mexicans who climbed the income ladder.

Their stories are revealing, not because they are typical, but precisely because they are so rare.

Less than 4% of Mexicans born outside the upper/middle classes ever reach the top 5% of income earners. This elite 5%, while still far from the global ultra-rich, sits in a realm of privilege within Mexico. Their average monthly income hovers around $120,000 USD annually (adjusted for purchasing power). That’s enough to place them well above the national average but still far from the wealth of Mexican billionaires like Carlos Slim. Even so, this group is largely inaccessible to those born outside of Mexico’s middle and upper-middle classes.

For those who do beat the odds, the routes to wealth tend to follow two main tracks: corporate ascension or entrepreneurial success. Other paths—public-sector work, academia, the arts—barely register.

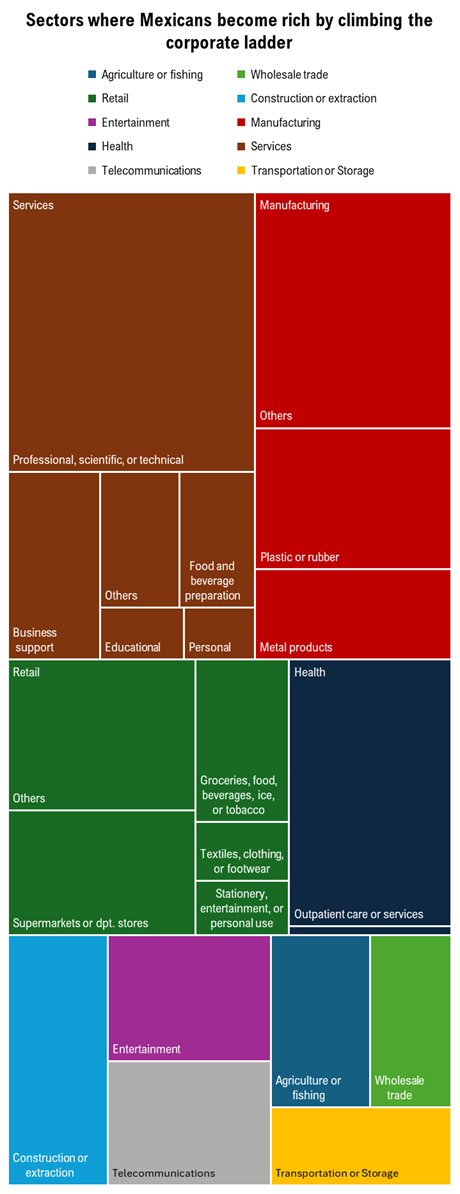

Route one: climbing the corporate ladder

Roughly half of Mexico’s new rich work in the formal private sector. They are, for the most part, executives in industries with high margins and formal contracts: finance, auditing, sales, manufacturing, health and retail.

Their career trajectories share common features. Most have technical university degrees in fields such as accounting, administration, or finance. They regularly live in Mexico City or closer to the American border where they can find well paid jobs in formal firms.

The sector that most enables Mexicans to reach the top income brackets is services, particularly professional services such as law, banking, and consulting.

But upward income mobility is also visible in manufacturing, retail, and healthcare, especially outpatient care. Within manufacturing, plastics and metal products stand out as industries with a strong track record of producing well-paid professionals. In retail, supermarkets and department stores have also proven to be reliable springboards for employees who eventually rise into the ranks of the newly rich.

What sets these professionals apart is not extraordinary talent or risk-taking, but stability. In a labor market dominated by informality (more than half of Mexican workers are in the informal sector), simply having a formal, upwardly mobile job is exceptional.

Interestingly, some of them have worked for the same employer for decades. In fact, 22% of the new rich that climbed the corporate ladder work at the same company that gave them their first job. Internal promotions, not job-hopping, built their wealth.

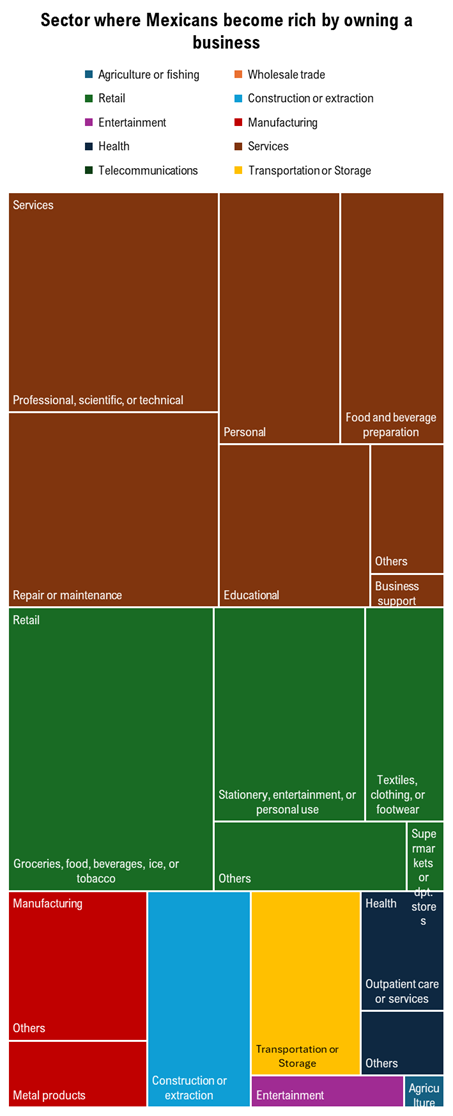

Route two: owning the right business

The other half of Mexico’s new rich are self-employed, mostly entrepreneurs. Unlike Silicon Valley mythology, they are not building billion-dollar tech start-ups in Mexico. The businesses that lead to wealth in Mexico are far more prosaic: retail shops, car dealerships, professional services, manufacturing firms, private school, restaurants, and sometimes even barbershops.

Services is the most common sector where people create their wealth followed by retail. While manufacturing and healthcare services are effective at producing newly rich employees, they are far less successful at producing newly rich entrepreneurs. Retail, by contrast, proves to be a far more accessible and fertile ground for wealth-building through entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurs who get rich tend to operate in sectors with high demand and low initial capital costs, and they usually keep operations lean. Many of them started in family businesses that their parents never managed to scale which they modernized and expanded. Very few grew up in poverty. One case cited in the survey involves a person who eventually opened a chain of successful hair salons.

Wealth entreprenerus are also more common in Mexico’s north, where proximity to the United States and better infrastructure increase the odds of commercial success. Although only 19% of Mexicans live near the U.S. border, nearly 30% of the country’s new rich do.

The geography of getting rich

Geography plays a decisive role in who gets rich in Mexico and how.

For entrepreneurs, the best places to build wealth are Mexico City and Puebla, which together account for 29% of all cases of newly rich business owners.

The capital’s dominance is expected: it is the country’s commercial and political center. Puebla’s role is more surprising, but likely tied to its history as a hub for manufacturing supply chains and small industrial enterprises, particularly in the automotive sector.

For employees, the geography shifts. The states with the highest concentration of newly rich workers are Guanajuato, Coahuila, Querétaro, Sinaloa, and Mexico City. Together, they account for 43% of upward mobility among salaried professionals.

The Bajío region (which includes Guanajuato and Querétaro) has benefited from decades of manufacturing expansion and service-sector growth, while Coahuila and Sinaloa have seen economic booms in agribusiness, mining, and logistics.

Nuevo León, and its capital Monterrey, warrant a separate mention. The state is often viewed as a beacon of entrepreneurship. Yet it accounts for just 5% of cases of newly rich individuals. There is plenty of wealth in Nuevo León, but most of it stays within established families. Monterrey generates rich people, yes, but far more through inherited capital than through new fortunes.

In fact, the northern border, particularly cities like Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, Tamaulipas, and Coahuila, has been more effective at creating new wealth than Monterrey. The region benefits from its proximity to the United States, more fluid trade, and dynamic cross-border economies that generate opportunity for business owners and employees alike.

Race and the skin tone of success

Finally, there is the question of race or, more precisely in Mexico’s context, skin tone. Among those who became rich through employment, lighter skin tones are overrepresented. In contrast, those who achieved wealth through entrepreneurship tend to more closely reflect the full spectrum of Mexico’s population, including darker-skinned individuals.

This disparity is not accidental. Decades of research have shown that Mexico’s labor market is shaped by colorism, a form of racial bias where lighter skin is socially and economically rewarded. Studies consistently find that people with lighter skin—especially women—are more likely to be hired, promoted, and paid better. The workplace, particularly in corporate environments, reflects and reproduces Mexico’s deep racial hierarchies.

Entrepreneurship offers a somewhat different route. Because it does not rely on being selected by hiring managers or fitting into elite corporate cultures, it allows for a broader range of social backgrounds. In this sense, Mexico’s business-owning newly rich are a more accurate reflection of the country’s racial and ethnic composition.

The paths that exist in Mexico to become rich say more about the country than they do about the individuals who succeed. Mexico’s tax structure is lenient toward capital and inheritance. The labor market is bifurcated between protected insiders and precarious outsiders. Public education is underfunded, and elite schooling is often the only reliable springboard into well-paying jobs.

Wealth, once attained, is rarely redistributed. Mexico has no inheritance tax, low property taxes, and limited capital gains enforcement. Once rich, staying rich is easy.

For the rare few who get there without being born into it, the lesson is clear: pick the right degree, stay in the formal sector, avoid large families, and, if possible, start a business in the north.

The Mexican dream exists—but it is narrow, selective, and unforgiving.

Great article Viri I really enjoyed it. It would be great if you write something equivalent, but in terms of how certain kind of education is a true factor getting rich, for instance: how valuable is a local masters degree vs one obtained overseas, public vs private education at university level, relevance of how recognized is a public university compared to smaller ones

Excellent analysis of how wealth is acquired in Mexico! Would someone in Mexico that has achieved Barista (partial financial independence) of the Financial Independence Retire Early (FIRE) movement be considered wealthy?