Mexico's Role in the U.S.-China Trade War

A fact about trade that Washington can’t afford to ignore

This piece is a special collaboration with César A. Hidalgo, Professor at the Toulouse School of Economics.

Last week, the United States and Mexico postponed a planned tariff hike that was set to take effect on November 1.

The postponement signaled that maybe Washington is acknowledging a key reality: that international trade is no longer a contest between nations, but a competition between blocs, and that within the North American bloc, Mexico is a key strategic partner.

Let’s unpack this a bit further.

Today, three key blocs dominate the global economy: North America, the European Union, and RCEP –the pact binding China to East and Southeast Asia.

North America is influential, but it is the lightweight of the trio. It exports $3 trillion annually, nearly half of which stays inside the region. The EU is larger, but it is also the most inward looking, with 59% of its exports remaining within EU borders. RCEP, by contrast, is the heavyweight and more outward looking of the three mega blocs. It ships more than $7 trillion to the world annually, with just 37% of its trade circulating internally.

In this global context, North America’s leverage is limited. Which is why Washington seems to be understanding that, if the U.S. wants to compete with RCEP and China, it must accept Mexico as a key strategic partner. This is because the United States and Mexico are not two countries involved in international trade, but two members of a highly integrated block where supply chains frequently cross the border.

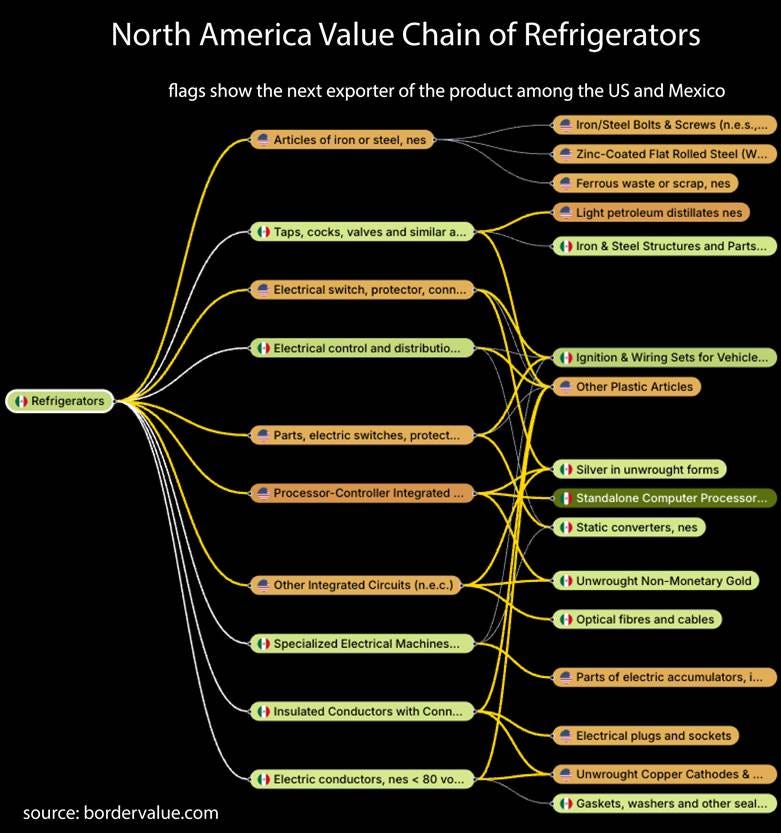

Take a comon household durable like refrigerators. This is a product with a value chain that involves multiple inputs, such as electrical control boards, switch protectors, and insulated conductors, among dozesn of others. More importantly, these inputs are expected to cross the U.S.-Mexico border multiple times.

According to data we released recently in Border Value, based on 2024 trade flows we expect the manufacture of refrigerators to involve 16 border crossings. This means that tariffs on products crossings the U.S.-Mexico border would not hit refrigerators once, but multiple times, as each time an input crosses the border, by itself or inside a more finished product, it would be hit by tariffs again.

But this is not a fact about refrigerators. For example, we can see that the manufacture of an air conditioning unit requires 11 border crossings; and that of a car requires even more.

These are not opinions, but hard facts illustrating the high level of integration of the North American economy. The ability of North America to compete with RCEP depends on keeping the team together. If these ripple effects are underappreciated, we risk disrupting supply chains that are essential for the competitiveness of the U.S. and Mexican economies.

The data is rather clear: tariffs within North America are at best friendly fire. If the U.S. and Mexico want to stay competitive, they’ll need to remember they’re playing on the same team.

César A. Hidalgo is a Professor at the Toulouse School of Economics, where he directs the Center for Collective Learning. His research explores how knowledge and information shape economic and social systems. He is the founder of Datawheel, creator of platforms such as the Observatory of Economic Complexity, Data USA, Data Mexico, and Border Value. Hidalgo is also the author of Why Information Grows and The Infinite Alphabet.

Ahhhh I wish this article were like 2000 words longer. Very helpful info!